Introduction

The purpose of this document is to address the questions and concerns most often raised by those considering the establishment of a commercial vineyard in Maryland. The pros and cons of such an undertaking, along with important factors such as site selection, winery requirements and economic considerations are discussed. Detailed information about the actual planting and maintenance of the vines is documented in a number of publications cited in Section VI.

While the material included here is intended for potential commercial growers, much of it will apply to the ‘backyard’ vineyardist as well.

There is a significant shortage of grapes in the state, and no relief is currently in sight. At present, supply is roughly 50% of demand.

Much of the fruit is purchased by local wineries, most of whom would readily expand if more grapes were available. As it is, Maryland laws restrict purchase of grapes from out-of-state sources unless it can be shown that local production is inadequate, or that the varieties sought are not available in Maryland. Most wineries prefer to buy Maryland grapes, but understandably make significant purchases elsewhere in order to meet the increasing demands of their customers.

There are a growing number of amateur wine-makers in Maryland who likewise find that their demand for grapes cannot be adequately met. They too turn to out-of-state markets, and even order grapes from the west coast to meet their needs.

The quality of Maryland grapes is generally high. It will be forever debated whether Maryland is a better place to grow grapes than Virginia, Pennsylvania, New York, etc, but no one questions the quality of the end product — the wines which are increasingly receiving world-wide recognition.

Much of the risk of grape growing in Maryland has been reduced in recent years, due to more and better information, the experience of pioneers in this field, and improvements in grape pest management. Grape growing provides a good alternative to crops whose future is in doubt, eg, tobacco, and a good adjunct to existing crops such as apples and peaches. Once established, a vineyard can provide a steady income.

On the debit side, no one is going to get rich quick by growing grapes. A heavy investment is required up front, and it could be 6-7 years before the venture starts turning a profit. The potential grape-grower is off to a good start if he already owns the land and some or all of the equipment required, such as tractor, sprayer, etc.

Also, grapevines demand more attention than many other fruit crops, especially during the growing season. And when winter pruning is factored in, it becomes quickly obvious that maintaining a commercial vineyard of more than 2-3 acres is more than a weekend activity.

Careful planning is a must. Vineyards are not established overnight, and rushing into decisions inevitably results in unnecessary expenditures and time-consuming reparations down the pike.

Site Selection

Wine quality begins in the vineyard, and proper site selection is an important factor in realizing this goal. High quality fruit can be, and is being, produced in vineyards situated on less-than-ideal locations, but the prospective vineyardist will save himself a lot of work and avoid numerous problems by choosing a site with favorable topography, soil and temperature conditions. No one site is going to provide the perfect combination of elements, but the fewer compromises the better.

The most significant factor relating to site suitability is the likelihood of dangerously low winter and spring temperatures. Excessively low winter temperatures can result in trunk damage and bud kill, especially in the more sensitive varieties. Sustained temperatures below -5 F are risky for these varieties.

In general, areas given to early fall frosts, spring frosts, excessive and frequent temperature shifts and sustained low winter temperatures should be avoided.

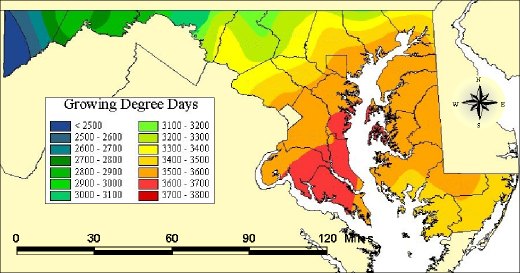

GLOBAL GIS CONSULTING – Savory@GISconsulting.com

The riskiest areas can be seen to include most of the northern portions of the state, especially in the western counties, with improving conditions toward Harford and Cecil Counties; and a ridge extending down through the center of the state, along the Carroll/Frederick, the Montgomery/Howard and the Prince Georges/Anne Arundel boarders. More moderate winter temperatures prevail along the Maryland/Delaware boarder and on either side of the Chesapeake Bay.

Topography plays a significant role in the quality and consistency of quality of wine grapes. In general, an elevation of 400 – 600 feet is best, with winter damage risk increasing with altitude (although by the same token the danger of early/late killing frosts decreases somewhat). Similarly, vineyards located on low pockets are vulnerable to frequent frosts. A gentle slope promotes good cold air drainage as long as there are no significant barriers to the flow. Steep slopes, however, pose problems for machinery and increase potential for erosion. A southern facing slope has the advantage of greater daily maximum temperatures and longer daily heating of fruit and vines. Fields which have been under crop cultivation in previous years offer the best potential for vineyard sites. Otherwise, the area should be cleared of large rocks, tree stumps, heavy brush, etc, then cultivated and planted in grass or grain for one or two years. Soil pH should be between 5.5 – 6.5, but can be adjusted by an application of lime (high pH soils are rare in Maryland).

Proximity to heavy woods can pose problems, as they harbor wildlife which feed on grapes or vine shoots — deer and birds are the worst offenders. A number of measures are available for crop protection, none of them entirely satisfactory. Also, proximity to fields in which 2-4D is used as an herbicide is risky, as drift from this pesticide can be extremely injurious to grapevines.

Soil types and suitability range widely throughout the state. Fortunately, grapevines are tolerant of what might be considered risky areas for other crops. They are grown in soils ranging from heavy clay to sand to shale and rock. Ideally, the soil will be loamy (approx equal proportions of sand, silt and clay), deep (30 – 40 inches of permeability) and well-drained, with moderate fertility. Too much fertility can result in excessive vegetative growth, whereas mildly deficient soil can encourage the vines to extend their root systems to greater depths, often resulting in higher quality fruit.

Soils which tend to be waterlogged, shallow, primarily heavy clay, hardpan (impervious subsoils which limit root penetration) and excessively acidic should be avoided. Sandy soils provide good aeration but have poor water retention, whereas clay soils have good water retention and nutrient supplies but poor aeration.

Where feasible, deep tilling with a subsoiler to a depth of at least 2′ prior to planting can be beneficial.

The primary nutrients for grapevines are nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, and to a lesser extent boron, calcium and magnesium. Soils severely deficient in any of these can be adjusted with applications of appropriate fertilizers.

Adequate precipitation has never been a serious problem in Maryland. Vine roots are capable of growing to considerable depths in search of water and nutrients. The only exception is newly-planted vines which may suffer in drought conditions and may need to be irrigated.

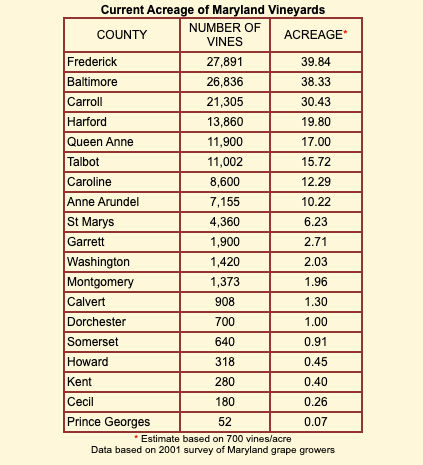

The following chart lists the counties with established vineyards, the numbers of vines planted, and the approximate acreage in each.

The choice of a variety/varieties to plant depends on a number of factors, such as market demand and site suitability. There are two main classifications of wine grapes: vinifera — the classic European varieties, such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, etc — and hybrid — crosses between vinifera and native American varieties, grown mostly in the eastern United States because they are more tolerant of difficult growing conditions. In general, hybrid vines offer the advantages of greater winter hardiness, ease of maintenance and higher yields. They are more forgiving of adverse conditions — one is nearly always assured of an adequate crop — and wine quality, when properly handled, can be quite good, especially among the white varieties, such as Seyval, Vidal and Vignoles.

The vinifera varieties range widely in terms of hardiness, with Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc usually exhibiting the fewest problems, and Chardonnay and Merlot the riskiest. Some popular varieties like Zinfandel and Pinot Noir perform poorly in this area.

It is generally agreed, however, that vinifera varieties at their best can produce quality wines competitive with those from Europe, the West Coast, etc. The fruit is also in much greater demand by local wineries and commands prices approximately double those of hybrids.

It should be noted that hybrids can be propagated from existing stock by simply rooting cuttings (derived from pruning), thus eliminating purchase costs, whereas vinifera varieties must be grafted onto rootstocks which are more tolerant of phylloxera, an insect which feeds of the roots of vinifera vines (this is true throughout most of the world). Choice of rootstocks is to some degree variety-dependent, and the prospective grower should consult qualified professionals once a grape variety has been selected.

Another factor is that yields from hybrids are often substantially higher than for viniferas. This, however, may be offset by increased cultivation and harvesting costs.

The safest recommendation in this sticky issue might be to start with one or two vinifera varieties along with one or more hybrid varieties to minimize the risk of total crop loss in a particularly severe year.

Winery Requirements

Most of the Maryland wineries grow some or all of their own grapes. A few of them use exclusively their own production, but most purchase grapes from independent growers. The quantity of winery-produced grapes remains fairly constant at this point, so expansion of their wine producing capacity depends upon increased availability from independent growers. Most wineries would like to expand, and the next few years may see additional wineries opening for business.

Over 300 tons of grapes are processed annually by Maryland wineries, of which roughly 30% are purchased. Based on current availability, the wineries who purchase grapes anticipate purchasing the same amount each year for the foreseeable future, but most would buy more if the right varieties were available.

The following is a list of winegrape varieties currently being used by Maryland wineries, followed by the approximate amount of each processed annually by the wineries (purchased both in and out of state), and the amount by which the wineries would like to increase production with these varieties.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While demand for certain varieties may vary, it seems safe to predict that any significant deviation from the established pattern is unlikely in the forseeable future. Recently there has been a modest increase in demand for certain hybrids, such as Chambourcin and Seyval, perhaps to fill the market for lower-priced wines. Vinifera grapes bring the highest prices, but the resulting wines are more costly and therefore face stiffer competition on the market.

In general, wineries prefer purchases of a ton or more of any particular variety, harvested and delivered in standard harvesting lugs (capacity approx. 30 lbs. ea). Fruit is expected to be of good quality, free from disease. Most wineries are able to process the grapes upon arrival so that lugs may be returned immediately. Prices will vary, depending upon variety — vinifera varieties currently bring $1200 – $1500 per ton, hybrids $500 – $700 per ton. Smaller quantities sold to amateur wine-makers are generally priced somewhat higher, and will vary depending on whether the fruit is sold already picked, pick-your-own, or already crushed. Harvest dates for this category are more flexible, and the buyer is usually expected to take delivery at the vineyard.

Presently, written contracts with wineries are not common. Wineries prefer to deal with growers on a long-term basis, with conditions agreed on at the outset.

Economic Considerations

The costs of vineyard establishment will vary widely, depending on a number of factors. A significant portion of the initial outlay will be alleviated if items such as land, and farm staples such as tractors and wagons, are already on hand. Total labor costs can be minimized if the vineyard owner does the work, or a significant part of it, himself. (One exception is harvest, which must be accomplished in a relatively brief time span and therefore requires additional labor forces).

It is advisable to start small and expand as needed. Minimal equipment is required for up to 3 acres, after which significantly larger equipment will be required.

Many of the expenses are one-time costs, such as site preparation, purchase of vines, trellis posts, etc. So the initial year’s outlay will appear rather formidable — although some of the costs, such as posts and trellis wire, can be spread out over, or even delayed until, the second year. Once the vines are established (usually the 3rd year), expenses should be fairly consistent.

The following budget chart is based on figures from several commercial vineyards of at least five acres in Maryland and Virginia, and assumes a hospitable site –ie, acceptable soil and weather conditions. Vine and trellis spacing differed somewhat in the vineyards sampled, but the costs were fairly consistent. The simplest trellis/wire configuration (2-wire double cordon) is assumed, although later addition of extra support wires is also factored in.

Labor costs are included, but not insurance, taxes, financing or data management time (marketing, sales, promotion, public relations, meetings, contract negotiations, etc). Labor is based on a rate of 7.50/hr, and amounts to approximately 40% of the total operating budget.

| Description | Expense | Income | Cumulative Net |

| Year One | $ 4,290 | 0 | – $ 4,290 |

| Year Two | $ 1,650 | 0 | – $ 5,940 |

| Year Three | $ 1,915 | $ 600.00 | – $ 7,255 |

| Year Four | $ 1,960 | $ 2,800.00 | – $ 6,415 |

| Year Five | $ 1,975 | $ 4,200.00 | – $ 4,190 |

| Year Six | $ 1,975 | $ 4,200.00 | – $ 1,965 |

| Year Seven | $ 1,975 | $ 4,200.00 | + $ 260 |

Capital Expenses

Where possible, items in this category were purchased used. It is worth noting that some of these items (eg, tree planter, post hole augers, etc) could also be rented. Farm machinery maintenance costs are included, but not time (labor) of maintenance. Vines in most cases were viniferas, so initial purchase costs were roughly double that for hybrids (again, purchase costs can be reduced or eliminated by propagating them from existing vine cuttings).

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| These figures constitute the heaviest expenditures, but will vary widely depending on whether any or all the items are already in hand, or whether they are purchased new or used. | ||||||||||||||||||||

Chronology

The following is a scenario of what takes place in a Maryland vineyard during a typical year.

JANUARY

Pruning begins in large vineyards. Hybrid varieties can be pruned earlier, vinifera varieties should be allowed to harden off as long as possible.

FEBRUARY

Pruning continues. Pre-emergent herbicides, if used, applied.

MARCH

Pruning completed. Cuttings collected and disposed of. Repairs to trellis made. New or replacement vines planted.

APRIL

Buds for current crop begin to push. Maintenance on vineyard equipment (tractor, mower, sprayer, etc) performed.

MAY

Bud-break. Spraying for fungus diseases initiated.

JUNE

Flowering begins. Shoots grow vigorously and are tied to trellis wires. Excess growth removed. Weeds sprayed or cultivated.

JULY

Growth continues at a rapid rate. Shoot thinning and hedging applied where necessary. Spraying with fungicides continues. Leaf pulling begun to prevent shading of grape clusters.

AUGUST

Grapes begin to take on color. Vine and grounds maintenance continue.

SEPTEMBER

Bird control measures activated. Early grape varieties harvested.

OCTOBER

Harvest continues. Post-harvest spray applied if needed.

NOVEMBER & DECEMBER

Vine leaves drop, wood hardens, vine lapses into dormancy and pruning of hybrid vines begun after hard frost.

Sources of Vines

Amberg Wine Cellars – New York – 315-462-3455

American Nursery – Box 87B1 – Madison, VA 22727 – 540-948-5064

California Grapevine Nursery – 1085 Galleron Road – St. Helena, CA 94574-9790

800-344-5688 – www.californiagrapevine.com

Concord Nurseries Inc – Foster Nurseries Division – 10175 Mileblock Rd

North Collins, NY 14111 – 800-223-2211 – www.concordnurseries.com

Double A Vineyards, Inc. – 10275 Christy Rd – Fredonia, NY 14063 – 716-672-8493

www.doubleavineyards.com

Duarte Nursery – 1555 Baldwin Road – Hugnson, CA 95326 – 1-800-GRAFTED

www.duartenursery.com

Foundation Plant Materials Service – University of California Davis – Davis, CA 95616

916-752-3590 – fpms.ucdavis.edu/Grape/GRAPEinfo.html

Grafted Grapevine Nursery – 2399 Wheat Rd. – Clifton Springs, NY 14432 – 315-462-3288

www.graftedgrapevines.com

Ison’s Nursery & Vineyards – Brooks, Georgia 30205 – 770-599-6970 – www.isons.com

Dr. Konstantin Frank Nursery – New York – 800-320-0735

www.drfrankwines.com/drfnursery.html

Quality Nursery – 303 Dalton Lane – Zillah, WA 98953 – 509-829-3326

grapeplants@earthlink.net

Mahonia Nursery – 4985 Battlecreek Rd – Salem, Oregon 97302 – 503-585-8789

www.mahonianursery.com

Sunridge Nurseries – 441 Vineland – Bakersfield, CA 93307 – 661-363-8463

www.sunridgenurseries.com/

Vinifera Grapevine Nursery – 8505 SW Creekside Place – Beaverton, OR 97008

800-648-1681

Vintage Nurseries – 27920 McCombs Avenue – Wasco, California 93280 – 1-800-499-9019

www.vintagenurseries.com

Hermann J. Wiemer – PO Box 38 – Dundee NY 14837 – 800-371-7971

www.wiemer.com

Reference

| Mid-Atlantic Winegrape Grower’s Guide – Publication # AG-535 Tony Wolf, PhD – E. Barclay Poling, PhD North Carolina State University, Campus Box 7603, Raleigh NC 27695 Available onlineMcGrew, J. Growing Wine Grapes, $12.50 American Wine Society 3006 Latta Rd. Rochester, NY 14612 716-225-7613 Wolf, T. Guide To Commercial Vineyard Establishment, Bulletin 463-018, $2.00 Wolf, T. Site Selection For Commercial Vineyards, Bulletin 463-016 (FREE) Wagner, P. Wine Growers Guide, Weaver, R. Grape Growing (Currently Out Of Print) Steiner, P. Maryland Commercial Small Fruit Production Guide Bulletin 242 (Updated Annually) Morton, L. Winegrowing In Eastern America |

| PERIODICALS |

| Practical Winery & Vineyard (Bi-Monthly) $30.00 15 Grande Paseo San Rafael, CA 94903Vineyard & Winery Management (Bi-Monthly) $25.00 P.O. Box 231 Watkins Glen, NY 14891 Wines & Vines (Monthly) $32.50 Wine East (Bi-Monthly) $18.00 |